Zoom Fatigue & The Rise (and Fall) of Clubhouse

Screen-related burnout drove the masses to go back to basics and talk on the phone using Clubhouse—an invite-only audio app that gained millions of new users in weeks. As people start socializing again, the question is, are those numbers sustainable?

Born from the pandemic, Clubhouse has seen a major dip in numbers recently—but big tech companies are still bullishly releasing their own versions of the app. With Zoom fatigue still plaguing millions, the continued push for audio apps makes a lot of sense...

Here we are. 2021: The year of COVID-19, Part 2. Businesses are opening up again little by little, there’s a vaccine-powered light at the end of the tunnel, and although a huge number of people are still working from home using Zoom and the like to hold meetings and interviews, it feels like there’s a massive shift away from using video calls for social purposes.

Eased restrictions and lower death and infection rates can, of course, be credited in large part with that shift, but I think a mass rejection of on-screen face time would’ve occurred even if we were as confined to our homes as we were a year ago.

It seems like we’re adding Zoom events to our calendars grudgingly at this point, only if we really feel obligated to. The era of packing our days with virtual surprise parties, bridal showers, baby showers, family reunions, happy hours, etc., etc., etc., is no longer—even if it’s been months since we’ve seen some of our friends, family, and certainly the acquaintances we’d scarcely get together with when things were “normal” anyway.

The Science Behind Zoom Fatigue

Zoom fatigue, the newly coined term used by researchers and journalists, is real, and if you haven’t read an article about it, you’ve at least seen a headline or a post about it on social media. It’s not just a buzzy SEO phrase, though. There’s science behind it that explains why we’re reluctant to turn our computer cameras on.

Sumner Norman, resident brain-machine interface researcher at AE Studio and postdoctoral fellow at Caltech, says that we have two reactions when communicating with each other face-to-face.

The first, Sumner says, occurs within milliseconds of registering another human’s face. We subconsciously mimic their expression—a process that plays a vital role in developing positive social relationships. He cites one study in which participants were subliminally exposed to an image of an angry, neutral, or happy face for just 30 milliseconds (.03 seconds). Despite the brief exposure, subjects who saw angry or happy faces reacted with distinct corresponding facial expressions.

The other reaction, Sumner says, happens a couple seconds later. That’s the one we consciously register—a smile, raised eyebrows, a dropped jaw that develops from our initial quick response. Luckily the internet runs fast enough for many of us to pick up on those reactions in real-time using popular video conferencing platforms.

“But if you're talking about a sub-50-millisecond reaction, now you're almost within the frame rate of computers,” says Sumner. Since video runs at a slower frame rate, there’s no way Zoom can pick up that first facial reaction fast enough.

Missing facial queues because of even the most diminutive internet latency causes us to lose an important, albeit tiny, part of the communication and connection-building process. Our brains are constantly searching for patterns to create a model and an understanding of the world around us. Communicating with a slight delay forces our brains to fill in the gaps to build those mental models, making the whole interaction more mentally demanding than we’re used to.

We miss out on more conspicuous queues too. Signs of engagement in a conversation, like head nodding or eye contact, give us positive reinforcement that tells us we’re being heard and makes speaking a lot easier.

“On Zoom, you're just talking to Hollywood Squares of faces that may or may not even be hearing you at all,” says Sumner. “I think your brain is constantly searching for validation that what you're saying is being heard and understood and felt in the way that you want it to be. When it's not, you're constantly trying to adjust the way that you speak, even though there's nothing actually wrong with it.”

Without real-time reactions and positive reinforcements, the faces in those squares sometimes stop feeling real. The phenomenon feels a lot like the uncanny valley effect (though research on this effect as it relates to Zoom doesn’t exist yet, as far as we know).

If you’ve seen the movie The Polar Express, you might’ve been inexplicably creeped out by it. Why did a heartwarming children’s tale about the magic of Christmas—starring Tom Hanks nonetheless!—feel creepy?

When it was released in 2004, the resemblance between the CGI characters and real human children was uncanny—creating an eerie feeling in viewers that some refer to as the uncanny valley effect. The theory is that objects like robots, realistic CGI animations, or even lifelike dolls become more appealing the more they resemble humans—but there’s a dangerous point when they become too humanlike. That’s when observers’ responses dip into this valley region, and they get super creeped out and repulsed.

It seems like a similar but less extreme effect would come from communicating with virtual humans day after day. We might not be completely creeped out and repulsed by the other people on a Zoom call (such a reaction would be pretttty rude), but we sometimes feel anxious and unsettled. Instead of the objects being too humanlike, the humans aren’t humanlike enough.

We definitely want humans to feel like humans so we can reap the benefits of social interaction. Humans evolved to be highly social creatures. The more we interact with others, the more we release the feel-good hormone oxytocin, which motivates us to seek out those interactions in the first place. We’re not quite getting the same effect from our Zoom interactions, for the reasons mentioned above (among other things), which might have us feeling even more disappointed because we’ve primed ourselves with the belief that virtual conversations will bring as much joy as in-person conversations once did.

“We went from a fully functioning world in which we were seeing a hundred people a week or a thousand people a week, whatever it is, to basically zero,” Sumner says. “You have this limited interaction that's really not quite clogging the giant hole.”

All of these science-backed factors have left many of us longing to fill the holes that video conferencing has created. And by “many of us,” we mean millions of people. The most current reports show 300 million users on Zoom and 100 million people using Google Meets every day.

The Return of Audio

Meanwhile, as we all started clicking links and joining Zoom meetings, invading each other’s most private spaces—bedrooms, kitchen tables, and for those of us with particularly boisterous partners, closets—a small Silicon Valley set was kicking it old school and chatting on the phone.

That set, around 1,500 people, was the first group of users on Clubhouse, a brand-new social networking platform based only on voice, launched in April 2020.

“When my friend first invited me, I was like, ‘Oh, this is just a bunch of Silicon bros tapping each other on the shoulder and congratulating each other,” said Dil-Dominé Leonares, a product designer and manager here at AE, and now an avid Clubhouse user who loves to talk NFTs and art. But once he spoke up in a “room” (one of the live conversations anyone on the app can jump in on), he realized how easy and natural it felt to participate in the conversation. When he began speaking up in more rooms, he saw his following grow by a couple thousand users in just a couple weeks.

Dil’s quick adoption and growth isn’t unlike the trajectory of many other users—and the app itself. According to app analytics company App Annie, Clubhouse spiked to 3.5 million users by February 1, 2021, and then to another 8 million by February 16.

The growth can be attributed in part to household names like Elon Musk and Oprah Winfrey, who joined the app, among other big-name celebrities. Users who joined rooms with them experienced a form of access we’ve never had before.

It was different than watching a major star on live television or even on Instagram Live, where there’s still a performance aspect involved with being on camera. Users were just hanging out on the phone with Elon Musk and Oprah! That incredibly personal, authentic experience had people hooked.

Though celebrity drop-ins contributed to the app’s success (Musk promised he’d bring Kanye West on, too), the rise of Clubhouse in tandem with the development of Zoom fatigue feels like no coincidence. “Sometimes you just want to get off video,” said Dil. Removing the pressure, anxiety, and mental effort involved with being on camera allows users to speak freely, with almost the same nonchalance they’d have in person. It’s a return to simpler times when landlines ruled the day and three-way calling ambushes were a thing.

“The beauty of audio is that when you take away the camera, you get a new level of authenticity. Clubhouse brings a level of transparency that our social media environment hasn’t had before,” Dil said, illuminating another refreshing aspect of Clubhouse.

A Clubhouse influencer isn’t the same as an Instagram or TikTok influencer. Follows aren’t based on filtered and curated images, selfie videos, or ads, which don’t exist on the app at all. More often than not, you’re following other users because you’ve heard them speak, you actually think they’ll add value to the rooms they’re in, you want to see which conversations they’re participating in, or you want to hear their opinions and ideas.

That seems to hold a lot more weight than a sponsored product promotion from someone who can film a high-quality video on the newest iPhone.

There’s a room for just about every interest and line of work, too. When you first log into Clubhouse through a personal invite—a feature that restricts who can and can’t join currently—you’ll scroll through and pick from a range of topics, sort of like Tumblr or Pinterest. Your “hallway,” the home screen that shows the different rooms you can join at any moment, populates based on your personal interests and who you follow.

You’ll hear people talking about cryptocurrency, space industrialization and commercialization, and sustainability. You can listen to conversations about Burning Man, psychedelics, being too broke for therapy, and a whole mélange of other subjects, much like in the podcast world. And as podcast listening continues to grow too, it makes sense that listeners would pivot to something more interactive while still maintaining the ease and freedom of being off-screen.

Clubhouse conversations are essentially podcasts but better because you can listen and respond in real-time.

It makes me think, again, of a bygone era when people would call up talk-radio shows in hopes of getting on air. Clubhouse borrows the same concept but makes it easier, tailored to your interests, and more personal.

This mass return to audio reinforces to us, a team of product designers, data scientists, and software developers, the idea that simpler is better. Sometimes we just need to think about the most basic human needs—the need for human connection, the desire to be heard and understood—and how we can meet them in the most agency-increasing way possible, simultaneously solving relevant problems. In the case of Clubhouse, that means reinstating authenticity in social connection, ending the current screen-fatigue pandemic (as that other pandemic hopefully comes to an end too), and driving a nostalgic return to the telephone.

Yet recent reports show Clubhouse downloads dropped by 72% last month—a drastic dip from the unexpected February surge. With major hubs for in-person networking like New York City and Los Angeles (formerly two of the most restricted areas of the country) announcing openings for Summer 2021, and 43.5% of the U.S. population at least partially vaccinated right now, the pandemic-born app has a lot working against it.

Can Clubhouse Keep Up?

Investors apparently aren’t worried. Andreessen Horowitz announced another round of series C funding on April 18, valuing Clubhouse at $4 billion. Meanwhile, other tech giants are still working hard to compete.

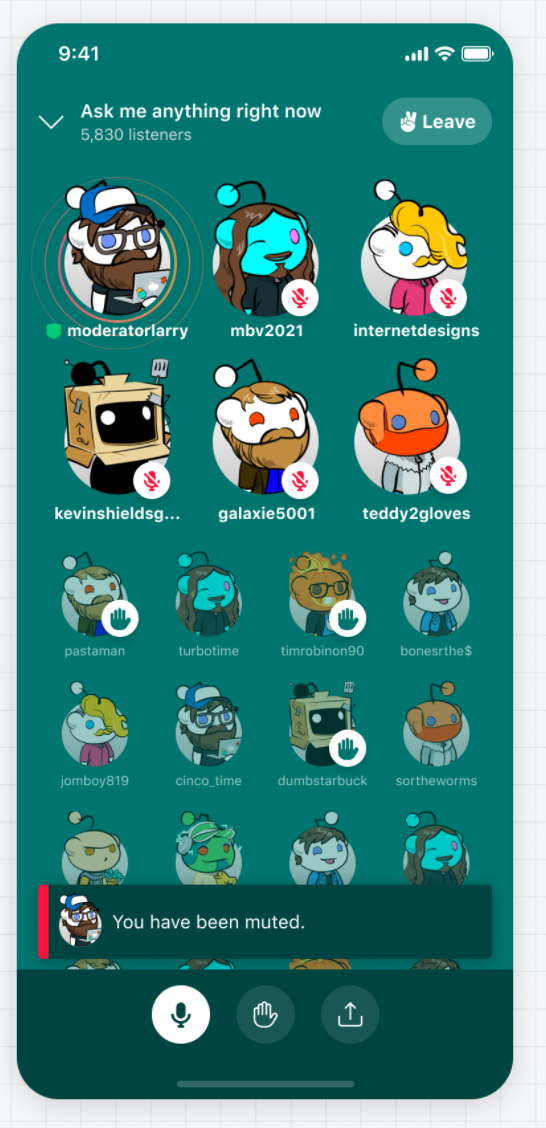

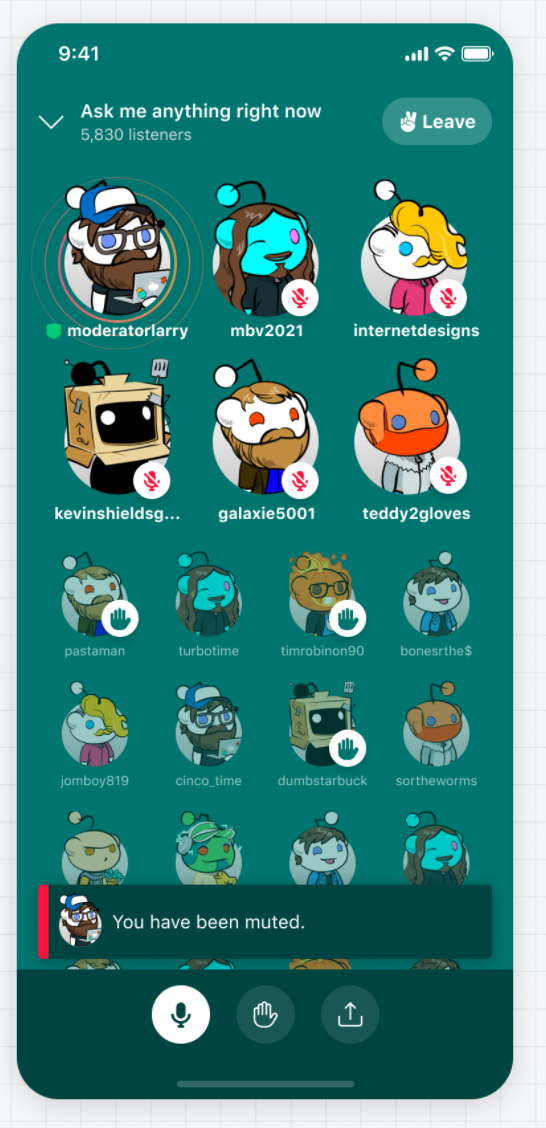

Reddit revealed its answer to Clubhouse, Reddit Talk, with a shockingly similar UI and concept: Live moderated talks that anyone can join. Sounds familiar. But Redditors are a loyal bunch and Reddit Talk conversations will live within subreddits which are easy to find, already have massive followings, and are more varied (and probably weirder) than what’s currently on Clubhouse, so they might be onto something.

Spaces is Twitter’s new launch, again an in-app live audio conversation feature. And Facebook just announced its own competitor, Live Audio Rooms, which will live in Facebook Groups, as well as a whole suite of audio-related features like in-app podcasts, sound clips like crickets or popular song lyrics that you can send to friends in WhatsApp or Messenger, and a Soundbite tool for creating short-form audio clips. Even Instagram, built to be purely image-centric, is pushing a Clubhouse clone, along with LinkedIn, Slack, and Spotify.

With major players in the game, audio is clearly back in a big way despite Clubhouse’s falling numbers. If media platforms weren’t thinking about audio before, they are now, and if they were already thinking about it, they’re stepping hard on the gas pedal.

Clubhouse may or may not fall behind, but it deserves kudos for creating exactly what millions of people needed when they couldn’t spend one more minute staring at a screen.

No one works with an agency just because they have a clever blog. To work with my colleagues, who spend their days developing software that turns your MVP into an IPO, rather than writing blog posts, click here (Then you can spend your time reading our content from your yacht / pied-a-terre). If you can’t afford to build an app, you can always learn how to succeed in tech by reading other essays.

Zoom Fatigue & The Rise (and Fall) of Clubhouse

Screen-related burnout drove the masses to go back to basics and talk on the phone using Clubhouse—an invite-only audio app that gained millions of new users in weeks. As people start socializing again, the question is, are those numbers sustainable?

Born from the pandemic, Clubhouse has seen a major dip in numbers recently—but big tech companies are still bullishly releasing their own versions of the app. With Zoom fatigue still plaguing millions, the continued push for audio apps makes a lot of sense...

Here we are. 2021: The year of COVID-19, Part 2. Businesses are opening up again little by little, there’s a vaccine-powered light at the end of the tunnel, and although a huge number of people are still working from home using Zoom and the like to hold meetings and interviews, it feels like there’s a massive shift away from using video calls for social purposes.

Eased restrictions and lower death and infection rates can, of course, be credited in large part with that shift, but I think a mass rejection of on-screen face time would’ve occurred even if we were as confined to our homes as we were a year ago.

It seems like we’re adding Zoom events to our calendars grudgingly at this point, only if we really feel obligated to. The era of packing our days with virtual surprise parties, bridal showers, baby showers, family reunions, happy hours, etc., etc., etc., is no longer—even if it’s been months since we’ve seen some of our friends, family, and certainly the acquaintances we’d scarcely get together with when things were “normal” anyway.

The Science Behind Zoom Fatigue

Zoom fatigue, the newly coined term used by researchers and journalists, is real, and if you haven’t read an article about it, you’ve at least seen a headline or a post about it on social media. It’s not just a buzzy SEO phrase, though. There’s science behind it that explains why we’re reluctant to turn our computer cameras on.

Sumner Norman, resident brain-machine interface researcher at AE Studio and postdoctoral fellow at Caltech, says that we have two reactions when communicating with each other face-to-face.

The first, Sumner says, occurs within milliseconds of registering another human’s face. We subconsciously mimic their expression—a process that plays a vital role in developing positive social relationships. He cites one study in which participants were subliminally exposed to an image of an angry, neutral, or happy face for just 30 milliseconds (.03 seconds). Despite the brief exposure, subjects who saw angry or happy faces reacted with distinct corresponding facial expressions.

The other reaction, Sumner says, happens a couple seconds later. That’s the one we consciously register—a smile, raised eyebrows, a dropped jaw that develops from our initial quick response. Luckily the internet runs fast enough for many of us to pick up on those reactions in real-time using popular video conferencing platforms.

“But if you're talking about a sub-50-millisecond reaction, now you're almost within the frame rate of computers,” says Sumner. Since video runs at a slower frame rate, there’s no way Zoom can pick up that first facial reaction fast enough.

Missing facial queues because of even the most diminutive internet latency causes us to lose an important, albeit tiny, part of the communication and connection-building process. Our brains are constantly searching for patterns to create a model and an understanding of the world around us. Communicating with a slight delay forces our brains to fill in the gaps to build those mental models, making the whole interaction more mentally demanding than we’re used to.

We miss out on more conspicuous queues too. Signs of engagement in a conversation, like head nodding or eye contact, give us positive reinforcement that tells us we’re being heard and makes speaking a lot easier.

“On Zoom, you're just talking to Hollywood Squares of faces that may or may not even be hearing you at all,” says Sumner. “I think your brain is constantly searching for validation that what you're saying is being heard and understood and felt in the way that you want it to be. When it's not, you're constantly trying to adjust the way that you speak, even though there's nothing actually wrong with it.”

Without real-time reactions and positive reinforcements, the faces in those squares sometimes stop feeling real. The phenomenon feels a lot like the uncanny valley effect (though research on this effect as it relates to Zoom doesn’t exist yet, as far as we know).

If you’ve seen the movie The Polar Express, you might’ve been inexplicably creeped out by it. Why did a heartwarming children’s tale about the magic of Christmas—starring Tom Hanks nonetheless!—feel creepy?

When it was released in 2004, the resemblance between the CGI characters and real human children was uncanny—creating an eerie feeling in viewers that some refer to as the uncanny valley effect. The theory is that objects like robots, realistic CGI animations, or even lifelike dolls become more appealing the more they resemble humans—but there’s a dangerous point when they become too humanlike. That’s when observers’ responses dip into this valley region, and they get super creeped out and repulsed.

It seems like a similar but less extreme effect would come from communicating with virtual humans day after day. We might not be completely creeped out and repulsed by the other people on a Zoom call (such a reaction would be pretttty rude), but we sometimes feel anxious and unsettled. Instead of the objects being too humanlike, the humans aren’t humanlike enough.

We definitely want humans to feel like humans so we can reap the benefits of social interaction. Humans evolved to be highly social creatures. The more we interact with others, the more we release the feel-good hormone oxytocin, which motivates us to seek out those interactions in the first place. We’re not quite getting the same effect from our Zoom interactions, for the reasons mentioned above (among other things), which might have us feeling even more disappointed because we’ve primed ourselves with the belief that virtual conversations will bring as much joy as in-person conversations once did.

“We went from a fully functioning world in which we were seeing a hundred people a week or a thousand people a week, whatever it is, to basically zero,” Sumner says. “You have this limited interaction that's really not quite clogging the giant hole.”

All of these science-backed factors have left many of us longing to fill the holes that video conferencing has created. And by “many of us,” we mean millions of people. The most current reports show 300 million users on Zoom and 100 million people using Google Meets every day.

The Return of Audio

Meanwhile, as we all started clicking links and joining Zoom meetings, invading each other’s most private spaces—bedrooms, kitchen tables, and for those of us with particularly boisterous partners, closets—a small Silicon Valley set was kicking it old school and chatting on the phone.

That set, around 1,500 people, was the first group of users on Clubhouse, a brand-new social networking platform based only on voice, launched in April 2020.

“When my friend first invited me, I was like, ‘Oh, this is just a bunch of Silicon bros tapping each other on the shoulder and congratulating each other,” said Dil-Dominé Leonares, a product designer and manager here at AE, and now an avid Clubhouse user who loves to talk NFTs and art. But once he spoke up in a “room” (one of the live conversations anyone on the app can jump in on), he realized how easy and natural it felt to participate in the conversation. When he began speaking up in more rooms, he saw his following grow by a couple thousand users in just a couple weeks.

Dil’s quick adoption and growth isn’t unlike the trajectory of many other users—and the app itself. According to app analytics company App Annie, Clubhouse spiked to 3.5 million users by February 1, 2021, and then to another 8 million by February 16.

The growth can be attributed in part to household names like Elon Musk and Oprah Winfrey, who joined the app, among other big-name celebrities. Users who joined rooms with them experienced a form of access we’ve never had before.

It was different than watching a major star on live television or even on Instagram Live, where there’s still a performance aspect involved with being on camera. Users were just hanging out on the phone with Elon Musk and Oprah! That incredibly personal, authentic experience had people hooked.

Though celebrity drop-ins contributed to the app’s success (Musk promised he’d bring Kanye West on, too), the rise of Clubhouse in tandem with the development of Zoom fatigue feels like no coincidence. “Sometimes you just want to get off video,” said Dil. Removing the pressure, anxiety, and mental effort involved with being on camera allows users to speak freely, with almost the same nonchalance they’d have in person. It’s a return to simpler times when landlines ruled the day and three-way calling ambushes were a thing.

“The beauty of audio is that when you take away the camera, you get a new level of authenticity. Clubhouse brings a level of transparency that our social media environment hasn’t had before,” Dil said, illuminating another refreshing aspect of Clubhouse.

A Clubhouse influencer isn’t the same as an Instagram or TikTok influencer. Follows aren’t based on filtered and curated images, selfie videos, or ads, which don’t exist on the app at all. More often than not, you’re following other users because you’ve heard them speak, you actually think they’ll add value to the rooms they’re in, you want to see which conversations they’re participating in, or you want to hear their opinions and ideas.

That seems to hold a lot more weight than a sponsored product promotion from someone who can film a high-quality video on the newest iPhone.

There’s a room for just about every interest and line of work, too. When you first log into Clubhouse through a personal invite—a feature that restricts who can and can’t join currently—you’ll scroll through and pick from a range of topics, sort of like Tumblr or Pinterest. Your “hallway,” the home screen that shows the different rooms you can join at any moment, populates based on your personal interests and who you follow.

You’ll hear people talking about cryptocurrency, space industrialization and commercialization, and sustainability. You can listen to conversations about Burning Man, psychedelics, being too broke for therapy, and a whole mélange of other subjects, much like in the podcast world. And as podcast listening continues to grow too, it makes sense that listeners would pivot to something more interactive while still maintaining the ease and freedom of being off-screen.

Clubhouse conversations are essentially podcasts but better because you can listen and respond in real-time.

It makes me think, again, of a bygone era when people would call up talk-radio shows in hopes of getting on air. Clubhouse borrows the same concept but makes it easier, tailored to your interests, and more personal.

This mass return to audio reinforces to us, a team of product designers, data scientists, and software developers, the idea that simpler is better. Sometimes we just need to think about the most basic human needs—the need for human connection, the desire to be heard and understood—and how we can meet them in the most agency-increasing way possible, simultaneously solving relevant problems. In the case of Clubhouse, that means reinstating authenticity in social connection, ending the current screen-fatigue pandemic (as that other pandemic hopefully comes to an end too), and driving a nostalgic return to the telephone.

Yet recent reports show Clubhouse downloads dropped by 72% last month—a drastic dip from the unexpected February surge. With major hubs for in-person networking like New York City and Los Angeles (formerly two of the most restricted areas of the country) announcing openings for Summer 2021, and 43.5% of the U.S. population at least partially vaccinated right now, the pandemic-born app has a lot working against it.

Can Clubhouse Keep Up?

Investors apparently aren’t worried. Andreessen Horowitz announced another round of series C funding on April 18, valuing Clubhouse at $4 billion. Meanwhile, other tech giants are still working hard to compete.

Reddit revealed its answer to Clubhouse, Reddit Talk, with a shockingly similar UI and concept: Live moderated talks that anyone can join. Sounds familiar. But Redditors are a loyal bunch and Reddit Talk conversations will live within subreddits which are easy to find, already have massive followings, and are more varied (and probably weirder) than what’s currently on Clubhouse, so they might be onto something.

Spaces is Twitter’s new launch, again an in-app live audio conversation feature. And Facebook just announced its own competitor, Live Audio Rooms, which will live in Facebook Groups, as well as a whole suite of audio-related features like in-app podcasts, sound clips like crickets or popular song lyrics that you can send to friends in WhatsApp or Messenger, and a Soundbite tool for creating short-form audio clips. Even Instagram, built to be purely image-centric, is pushing a Clubhouse clone, along with LinkedIn, Slack, and Spotify.

With major players in the game, audio is clearly back in a big way despite Clubhouse’s falling numbers. If media platforms weren’t thinking about audio before, they are now, and if they were already thinking about it, they’re stepping hard on the gas pedal.

Clubhouse may or may not fall behind, but it deserves kudos for creating exactly what millions of people needed when they couldn’t spend one more minute staring at a screen.